Summary

This week marks a decade since the ALBA-1 submarine cable began carrying traffic between Cuba and the global internet. And last month’s recommendation by the US Department of Justice to deny the request by the ARCOS cable system to connect Cuba shows that, almost a decade later, geopolitics continues to shape the physical internet — especially when it comes to Cuba.

The views expressed in the following article are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.

This week marks a decade since the ALBA-1 submarine cable began carrying traffic between Cuba and the global internet. On 20 January 2013, I published the first evidence of this historic subsea cable activation which enabled Cuba to finally break its dependence on geostationary satellite service for the country’s international connectivity.

ALBA-1 was one of my first lessons on how geopolitics can shape the physical internet.

Last month’s recommendation by the US Department of Justice to deny the request by the ARCOS cable system to connect Cuba shows that, almost a decade later, geopolitics continues to shape the physical internet — especially when it comes to Cuba.

The ALBA-1 activation

I first learned of the mystery of the ALBA-1 submarine cable from The Internet in Cuba blog of Larry Press, computer science professor at California State University, Dominguez Hills. At that time, the cable had reportedly been constructed but was inexplicably laying dormant for over a year, prompting intense suspicion and speculation about its status.

As the world became more connected, Cuba had been excluded from every previous submarine cable system in the Caribbean due to the U.S. embargo against the communist nation. As a result, the Cuban internet was completely dependent on geostationary satellites to reach the outside world. In contrast to undersea fiber optics, geostationary satellite service offers lower capacity with significantly higher latencies, all at a higher cost per Mb — not great for a developing nation’s sole source of internet service.

Ultimately, it was the Venezuelan government (ally to Cuba and adversary to the U.S.) that put up the money to build a submarine cable to improve Cuba’s connection to the internet. In 2007, a joint Cuba-Venezuela venture announced its intention to construct an undersea fiber optic cable to Cuba by 2009.

The ALBA (Alternativa Bolivariana para los Pueblos de nuestra América) cable experienced numerous delays but was eventually designated RFS (ready-for-service) in February 2011. However, as the months progressed, there remained no evidence that the new cable had made any difference for the Cuban internet. It was a mystery closely followed by Cuba watchers everywhere.

I configured my internet monitoring tools to look for any new connection into Cuba, and a year later, it found one — a new BGP adjacency between Cuban state telecom ETECSA (AS11960) and Spanish telecom giant Telefonica (AS12956). When I checked our active measurements into Cuba that traversed this new link, we observed latencies that were impossibly low for a round-trip time over geostationary satellite.

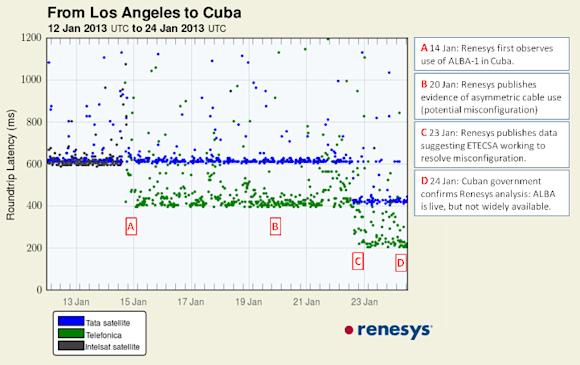

This graphic from my presentation at NANOG 57 in February 2013 captures the migration of latency measurements to Cuba observed from one of Renesys’s measurement servers.

When we published our initial report on the ALBA-1 activation, we speculated on why the latencies weren’t even lower than what we were observing:

We believe it is likely that Telefonica's service to ETECSA is, either by design or misconfiguration, using its new cable asymmetrically (i.e., for traffic in only one direction).

This misconfiguration appeared to have been resolved when the latencies dropped further a few days later. During my participation in LACNIC 19 in Medellin, Colombia, a few months later, I was introduced to the Director of ETECSA, who confessed that his engineers fixed the asymmetric routing snafu after seeing my blog post. You never know who’s reading your stuff!

In the intervening decade, internet adoption in Cuba grew at an anemic pace: from relying on internet cafes and wifi hotspots to the eventual activation of 3G mobile service in December 2018. But adoption grew enough to enable Cubans to start enjoying a freedom of communication that many in other countries around the world expect and sometimes take for granted.

In fact, the internet became important enough that the Cuban government began cutting service following the largest anti-government protests in decades in the summer of 2021. While Cuba has been a repressive state for many years, it wasn’t until the past two years that the country felt the need to shut down services to counteract protests. Maybe that’s progress.

Blocking the ARCOS segment to Cuba

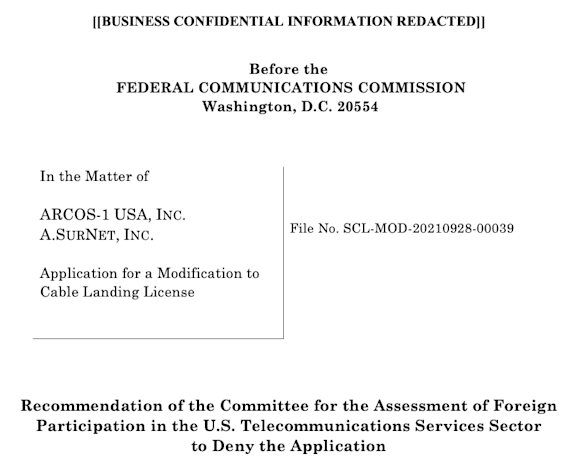

The latest chapter in the saga of the Cuban internet came last month, when the US Department of Justice’s Team Telecom published their recommendation that the FCC deny a request by the ARCOS submarine cable system to add a segment that would connect Cuba to the cable. According to their recommendation, building such an extension would create “immitigable risks to the national security and law enforcement interests of the United States.”

Unfortunately, the technical rationales provided in the published decision reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of how the logical internet and its underlying physical infrastructure work together. It is safe to say that as a result of this recommendation, the ARCOS cable will not build a segment to Cuba, leaving the country almost completely reliant on a single submarine cable.

The recommendation describes the government of Cuba as “a foreign adversary that poses a national security threat to the United States.” Make no mistake; the Cuban government is an authoritarian regime that represses political dissent, and the two countries’ governments have been adversaries for decades. As the recommendation states, the Cuban government censors its internet and has shut down service in response to anti-government protests. All true statements.

Be that as it may, the argument that adding a Cuban segment to the ARCOS cable system poses “immitigable risks” to the United States’ national security falls flat. Let’s look at some key pieces of that argument.

The Cuban government could soon glean communications, travel records, health records, credit information and any other information transiting Segment 26, and share that information with [China]...

The recommendation states that if the segment were built, Cuban state telecom ETECSA would control the cable landing station and therefore be in a position to intercept any US internet traffic traversing the segment. The truth is that ETECSA owns and operates all of the telecommunications infrastructure in Cuba. Therefore, all internet traffic entering or leaving the country could be at risk of interception by the Cuban government. This is true today, whether or not Cuba gets a submarine cable directly linking it to the United States.

ETECSA could also take advantage of these vulnerabilities to cause BGP route leaks, leading traffic not destined for Cuba to be misrouted over Segment 26 and into the Cuban government’s hands.

The recommendation argues that a submarine cable directly linking the United States to Cuba would somehow enable BGP hijacks – a topic I have researched extensively for more than a decade. In fact, to bolster its case, the recommendation cites the FCC’s decision to revoke China Telecom’s license to operate in the US due to reported incidents of traffic misdirection due to BGP vulnerabilities. That FCC decision cited my work over the years documenting these incidents, so I have some bona fides on this matter.

Regardless, a submarine cable alone cannot enable a BGP hijack. The only thing that stops ETECSA (or any telecom) from performing BGP hijacks today are route filtering by its transit providers and routing security mechanisms such as RPKI ROV. A submarine cable directly linking Cuba to the United States does not increase the possibility of a BGP hijack from Cuba.

ETECSA could manipulate routing information upstream so that more data transits Cuba instead of other routes, including by offering low-or-no-cost transit to small internet providers to entice traffic to transit Segment 26 into Cuba.

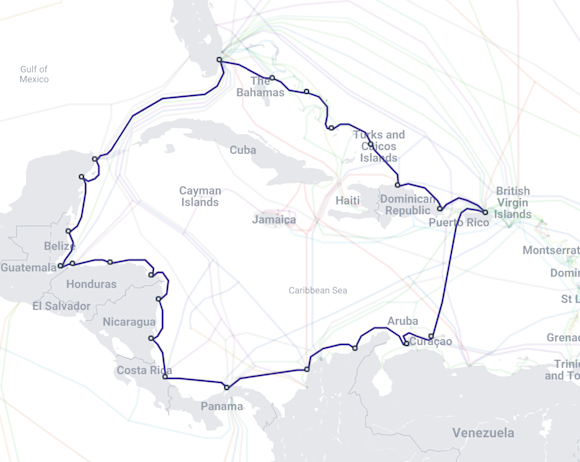

Lastly, the recommendation describes scenarios in which internet traffic in the Caribbean could be re-routed through ETECSA. The first scenario hypothesizes that if ETECSA started selling transit to other Caribbean telecoms (supposedly at a greatly reduced cost — ostensibly subsidized by China), then they could attract non-Cuban traffic through their infrastructure, putting it at risk of interception. Secondly, ETECSA could use its connection to ARCOS to directly exchange traffic with other telecoms in the Caribbean, and those connections could double as backup links for other telecoms in the region. Activating a link to ETECSA as a backup would risk the interception of non-Cuban traffic.

Either of these hypothetical scenarios could have already taken place but haven’t. Recall that ALBA-1 is a cable “system,” meaning that it is made up of two submarine cables: one to Venezuela and one to Jamaica. In fact, for several weeks in 2013, ETECSA was using the Jamaica segment to attain transit from Cable & Wireless Jamaica. Nothing is stopping ETECSA from peering with Jamaican providers today to offer cheap transit or a backup route in case of a cable failure.

Conclusion

In my opinion, the technical basis for Team Telecom’s recommendation to deny ARCOS’s request to build a segment to Cuba is flimsy but perhaps unsurprising — why help an adversary improve their internet service?

However, in my opinion, limiting Cuba’s international connectivity is not in the interest of the Cuban people nor the United States, whose Cuba Internet Task Force’s top recommendation in 2018 was the “construction of a new submarine cable.” Blocking such a cable runs counter to the US’s purported support for greater internet connectivity in Cuba as well as the national interests of both countries.

Cuba’s dependence on a single submarine cable is a risk to the internet of Cuba and, ultimately, the Cuban people. A second submarine cable to Cuba would offer the benefits of lower latencies to the United States and neighboring Caribbean countries, increased bandwidth capacity to the global internet in general, and greater resiliency in the event of a submarine cable failure.

Help appears to be on the way for the internet of Cuba. Immediately following the publication of DoJ’s recommendation to reject ARCOS’s segment to Cuba, ETECSA announced a deal with French incumbent Orange to build a submarine cable to Martinique. The proposed Arimao submarine cable will span over 2400 km and be the first new submarine cable to connect to Cuba (that doesn’t land at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base) in over a dozen years.

Crafting effective policy towards adversarial nations is no easy task. Still, there is a growing consensus within the digital rights space that any measures to restrict internet and telecommunications are counterproductive. Case in point is the recent decision by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to modify sanctions against Iran to explicitly allow cloud providers such as Google to provide free services in Iran. If we sincerely want to support the people of countries like Cuba and Iran, I think that would should encourage, not block, initiatives that would improve the reliability of their internet access.

See Yucabyte’s terrific Twitter thread (en Español) on the history of connectivity between the US and Cuba.