What Caused the Red Sea Submarine Cable Cuts?

Summary

In the latest collision between geopolitics and the physical internet, three major submarine cables in the Red Sea were cut last month likely as a result of attacks by Houthi militants in Yemen on passing merchant vessels. In this post, we review the situation and delve into some of the observable impacts of the subsea cable cuts.

On February 24, three submarine cables were cut in the Red Sea (Seacom/TGN-EA, EIG, and AAE-1) disrupting internet traffic for service providers from East Africa to Southeast Asia. For a variety of factors, the Red Sea has been a dangerous place for submarine cables over the years, but with a hostile party firing missiles at nearby seafaring vessels, it has recently become even more so.

In this post, we will review the background of the unique situation in the Red Sea and go into the internet impacts and timings of the submarine cable cuts. This work has been done in collaboration with WIRED magazine who is simultaneously publishing their own investigation into the cable cuts.

Background

In response to the ongoing war in Gaza, the Houthi-controlled Yemeni government began firing missiles and armed drones at ships transiting the nearby Bab al-Mandab strait that they believe have some affiliation with Israel, Britain, or the United States.

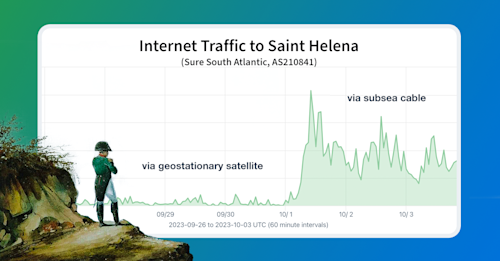

In November, missiles were fired from Yemen at Israel’s key Red Sea shipping port of Eilat. Shortly afterward, YemenNet suffered a multi-hour outage, leading to speculation that the internet blackout was retaliation for the missile strike. I described this episode in the conclusion of a blog post calling for greater transparency within the submarine cable industry, because, according to cable owner GCX, the YemenNet outage was caused by scheduled maintenance.

In late December, a post in a Houthi-allied Telegram channel suggested that the submarine cables could also become targets of their retaliatory attacks on behalf of Gazans. However, after the threat was widely reported by the media, the Houthi-controlled Yemen Ministry of Telecommunications published a statement disavowing any targeting of submarine cables:

“The (Ministry of Telecommunications) disclaims what has been published by the social media and other media … with regard to the so-called threats against the Submarine Cables that cross Bab al-Mandeb in the Red Sea-Yemen.”

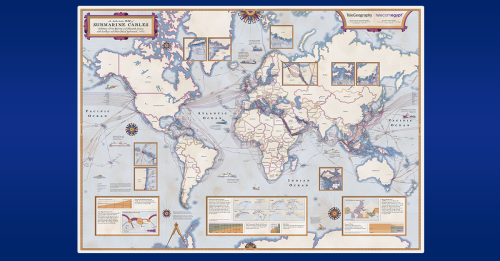

A dangerous place for submarine cables

In June 2022, I published a blog post discussing Egypt’s role as a chokepoint for global internet communications. However, this chokepoint extends through the neighboring Red Sea which offers its own set of risks.

Cargo vessels in the Red Sea awaiting their turn to traverse the nearby Suez Canal will drop anchor in the sea inlet’s relatively shallow depths. The possibility of an anchor snagging one or more submarine cables is very real and has occurred in the past.

In February 2012, three submarine cables were cut in the Red Sea due to a ship dragging its anchor. At the time, I wrote about the impacts on internet connectivity in East Africa, focusing on how much connectivity had survived what would have previously been a cause for a complete communications blackout in the region.

What happened on February 24?

Three submarine cables suffered cuts on the morning of Saturday, February 24: EIG, Seacom/TGN-EA, and AAE-1. According to industry sources, EIG was already down at the time due to a previous cut which occurred in early December, so the operational impact on internet communications of a second cut was minimal.

Seacom, to their great credit, continued its practice of being one of the most open and communicative submarine cables in the world by immediately confirming the damage sustained to their cable. EIG and AAE-1 have not published anything similar.

Initial speculation of the cause of the cuts focused on the purported threats against submarine cables posted in the Telegram channel from December. How Yemen would have pulled off such an undersea attack was left unexplained: underwater explosives, divers with cutting gear, a submersible?

Before long, a more realistic theory emerged from the submarine cable industry. Days before the three subsea cable failures, a Belize-flagged, United Kingdom-owned cargo ship was struck by missiles fired from Yemen. The crew dropped anchor and abandoned the crippled ship, the MV Rubymar. Afterwards, the Rubymar began to drift, dragging its anchor — one of the top causes of submarine cable cuts according to the International Cable Protection Committee. On March 2, the derelict vessel finally sank, taking with it more than 41,000 tons of fertilizer.

Yet to be confirmed, the dragging of the Rubymar’s anchor remains the leading theory as to the cause of the submarine cable cuts on February 24. For their part, the Yemen Ministry of Telecommunications released a statement denying involvement in cutting the cables.

Operational internet impacts

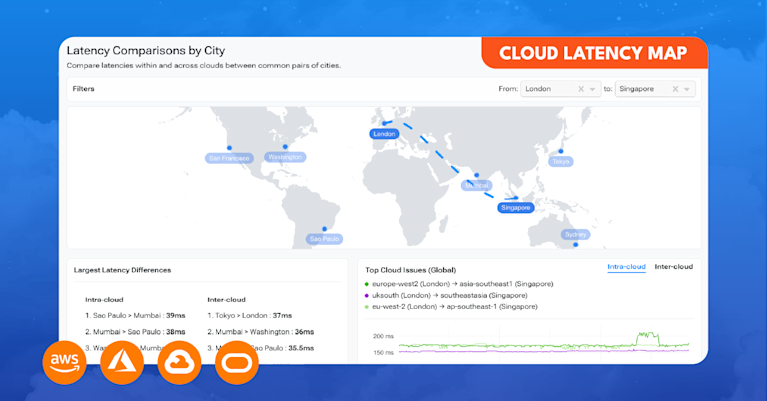

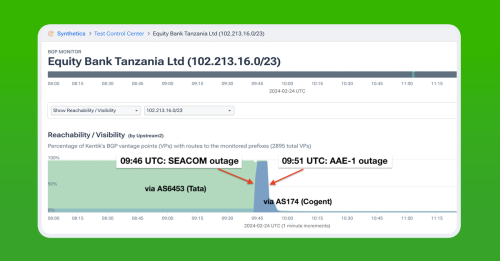

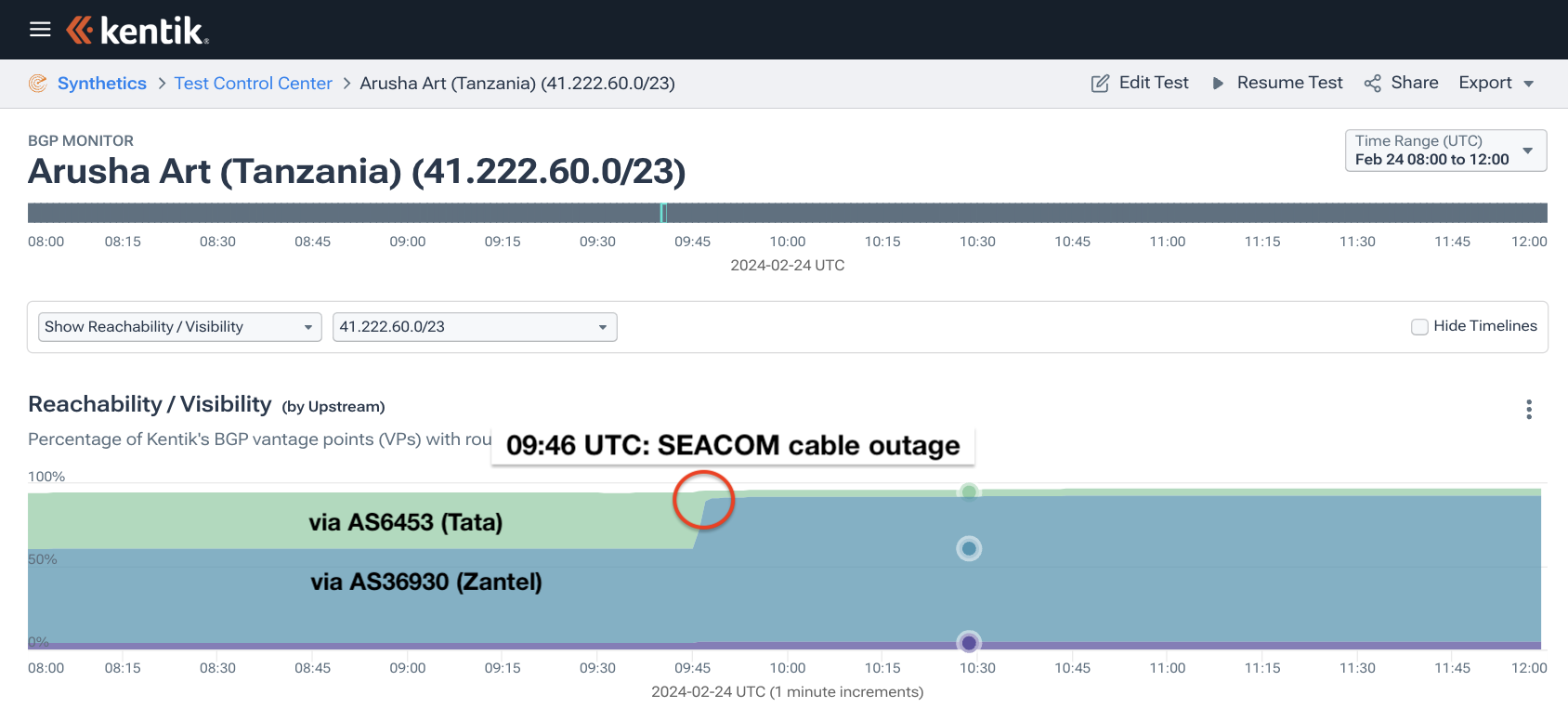

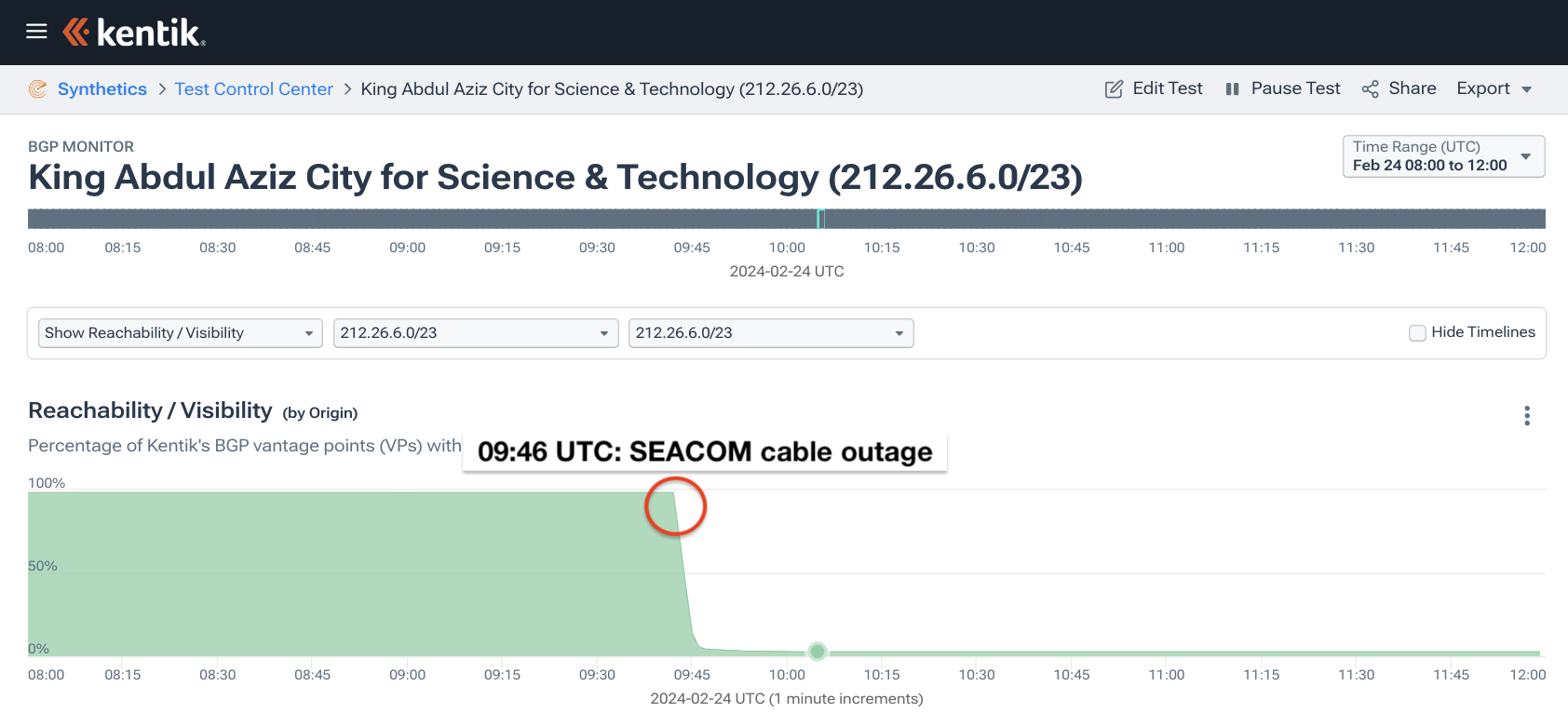

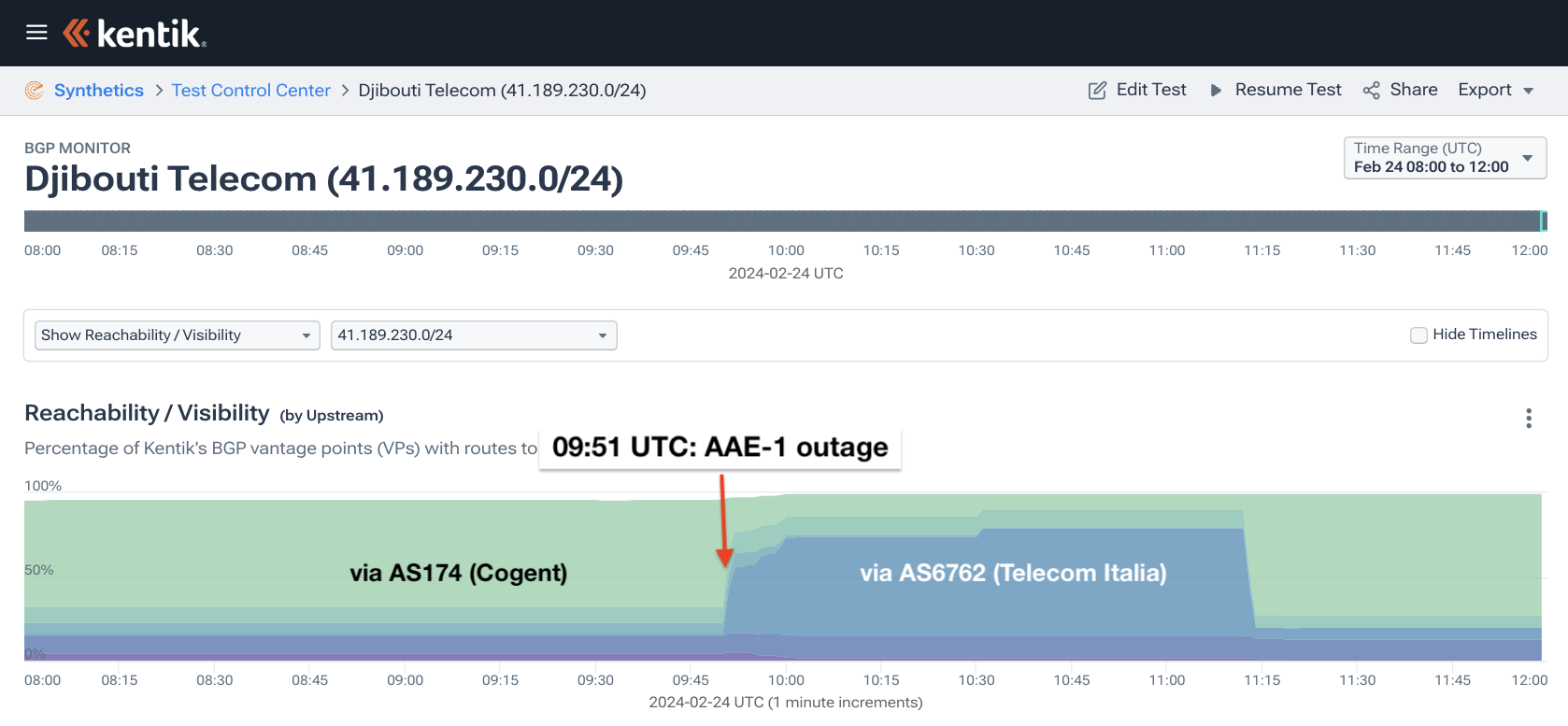

As mentioned earlier, the EIG was already out of commission, so we don’t expect to see an impact from its loss in Internet measurement data, but the losses of Seacom and AAE-1 were observable. In fact, due to the different geographies of these cables, I believe I have been able to infer the timings of each cable cut. There were two clear clusters of disruptions occurring at 09:46 UTC and again around 09:51 UTC — about five minutes apart.

Tata is a part owner of the Seacom cable, and, during its lifetime, the cable has been Tata’s preferred way to provides international transit to its customers in East Africa. Disruptions in East Africa, often involving the loss of Tata transit, occurred at 09:46 UTC. Therefore, I believe that is when Seacom suffered its failure.

Conversely, the second cluster of disruptions around 09:51 UTC primarily occurred along the path of AAE-1 from the Red Sea to Asia, although we also saw impacts in East Africa. Therefore, I believe AAE-1 suffered its failure several minutes after the Seacom cut.

Let’s look at some impacts visible in various types of measurement data, beginning with some Kentik BGP visualizations.

Below is a BGP visualization of the percentage of BGP sources that saw each upstream of Arusha Art (AS37143) over time for 41.222.60.0/23. The route wasn’t withdrawn, but AS37143 lost service from Tata (AS6453) at the estimated time of the Seacom cable cut.

King Abdul Aziz City for Science & Technology (AS8895) was exclusively transited by Tata (AS6453) but was withdrawn at 09:46 UTC when Seacom went down.

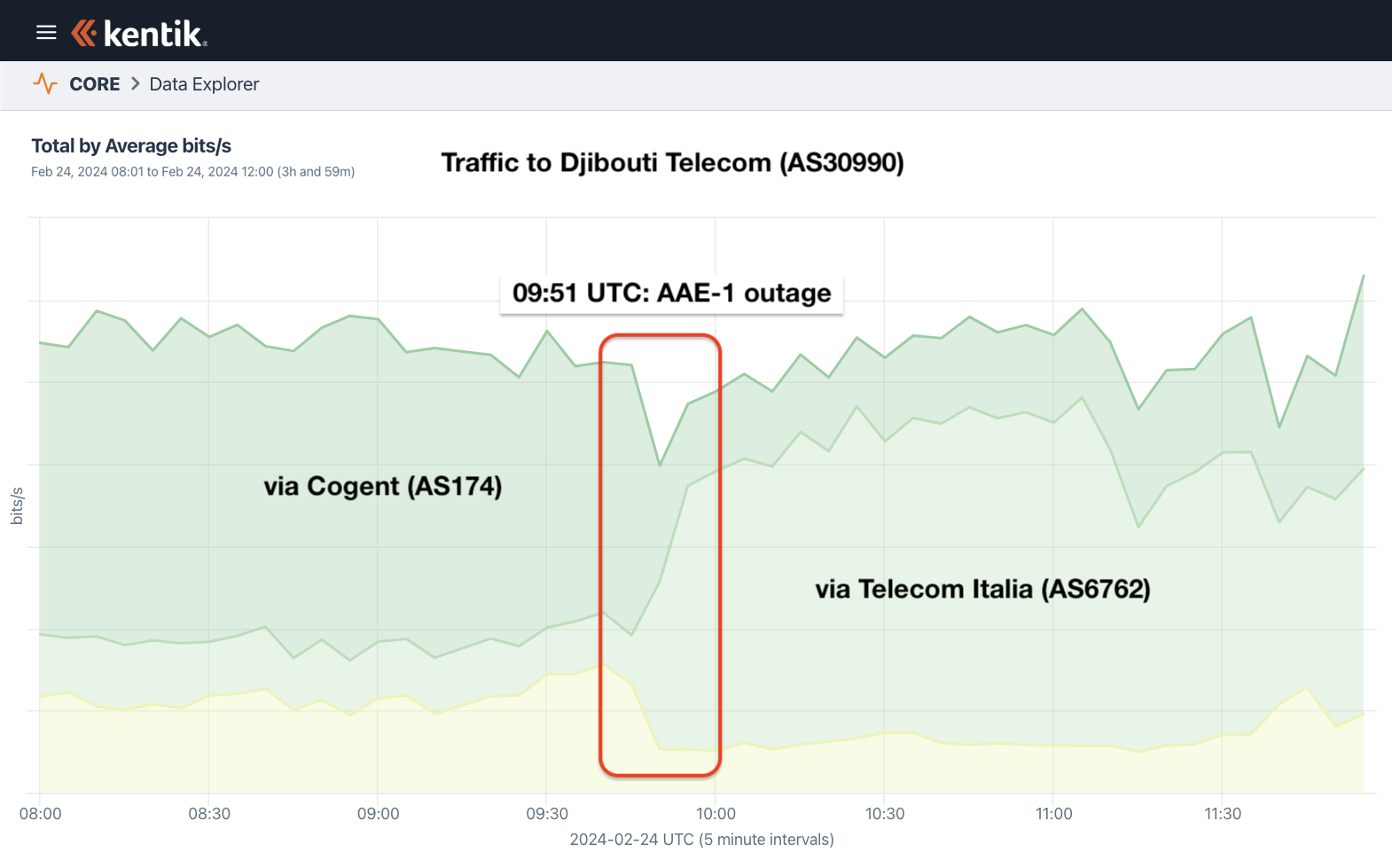

In the graphic below, we can see the shift of transit experienced by Djibouti Telecom with the loss of the AAE-1 cable. Looking upstream from AS30990 (Djibouti Telecom), the primary change is a loss of Cogent (AS174) replaced by AS6762 (Telecom Italia) until the Cogent service is restored through another cable hours later.

The transit shift depicted by the BGP visualization above is also reflected in Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow, pictured below.

The graphic below illustrates the transit shift for a route originated by Etisalat in the UAE. When looking at the upstreams of AS8966 (Etisalat) for this route, transit from AS1299 (Arelion) and AS2914 (NTT) was lost at 09:51 UTC when AAE-1 suffered a cut. According to our BGP data, the loss was replaced by transit from AS6762 (Telecom Italia), AS7473 (Singtel) and expanded service from AS3356 (Lumen).

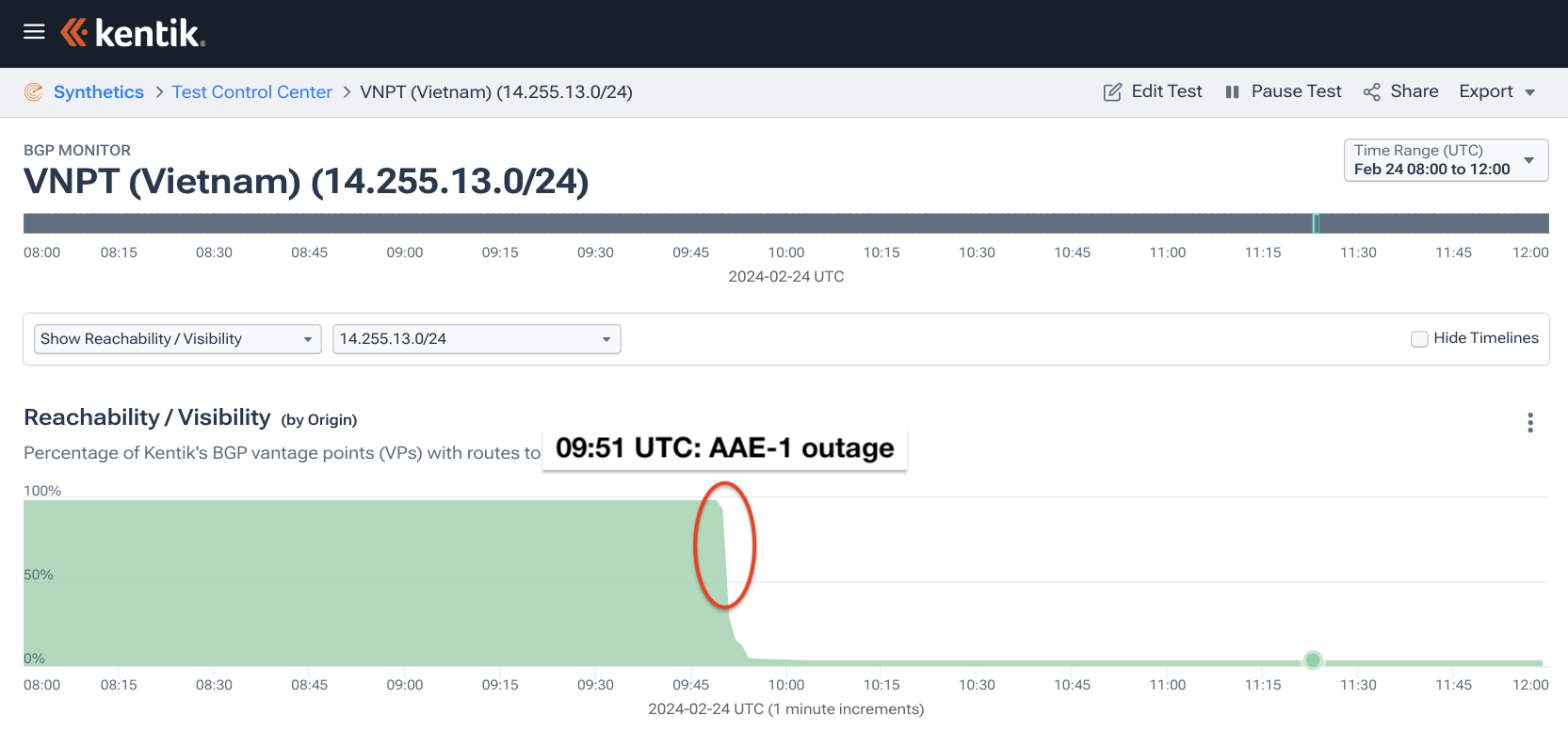

Impacts from the AAE-1 cable cut can be observed all the way out in Southeast Asia. Vietnamese incumbent VNPT (AS45899) had routes withdrawn at the time of the cable cut, such as the one illustrated below.

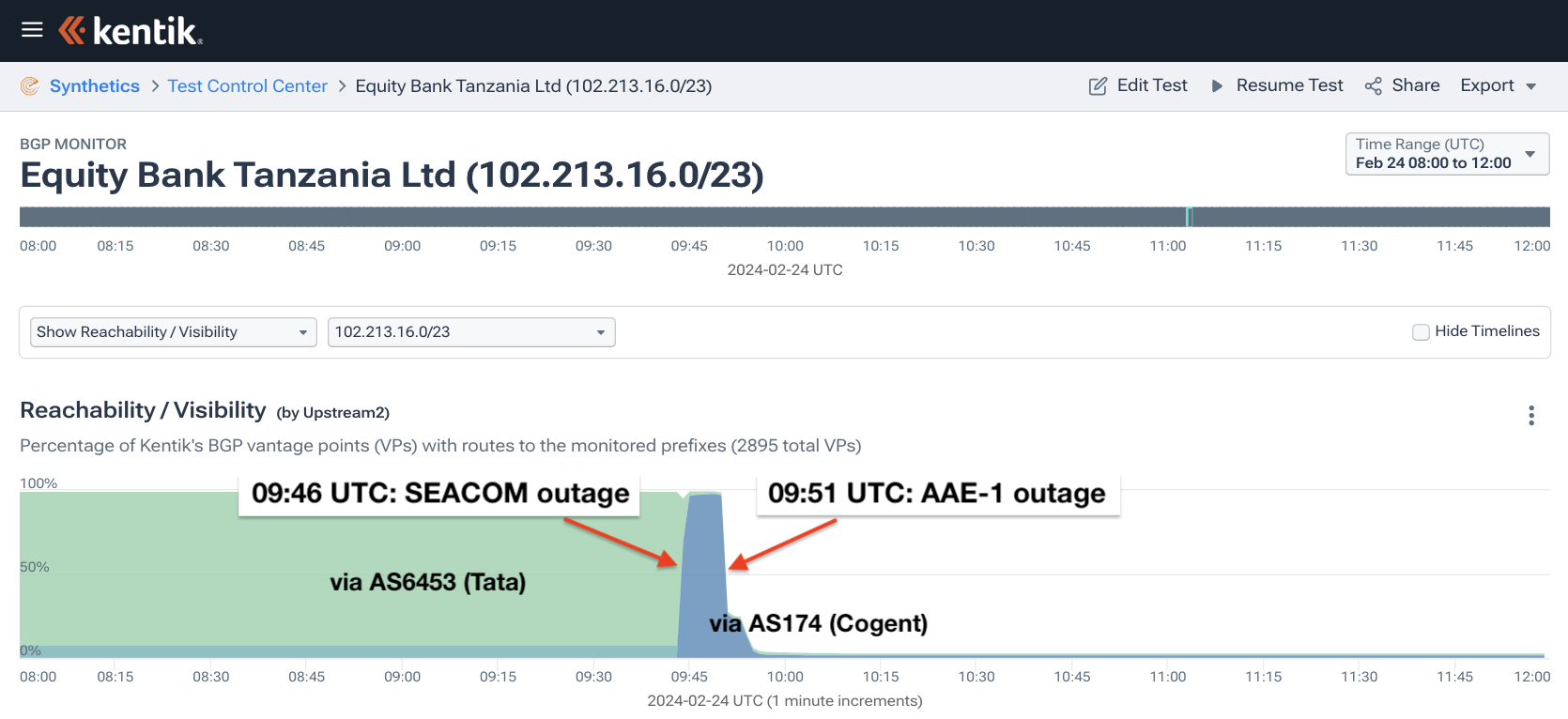

And finally, here is an example of a route that appears to have been downstream of both severed cables. 102.213.16.0/23 (Equity Bank Tanzania) is originated by AS329242 and transited exclusively by Simbanet (AS37084). Below is an upstream view for AS37084, showing the loss of Tata (AS6453) service when the Seacom cable was cut, followed minutes later by the loss of Cogent (AS174) when AAE-1 went down.

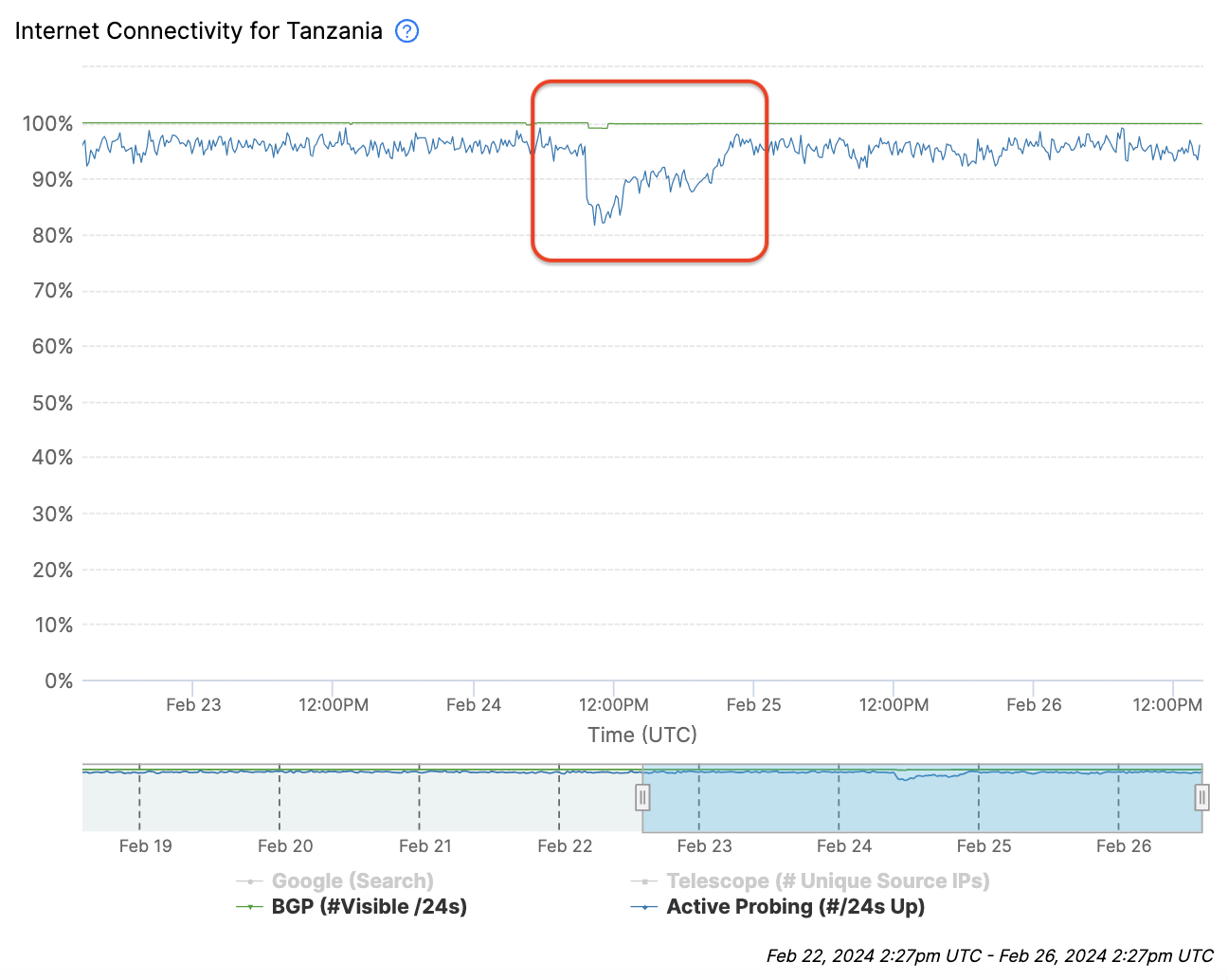

Additionally, Georgia Tech’s IODA tool reported drops in active measurement to countries in East Africa, including Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Mozambique, around 09:50 UTC, likely due to the loss of the Seacom cable.

Conclusion

While the Red Sea has been a problem area for submarine cables for many years, the current situation is quite unique. Never before has a hostile actor repeatedly fired at vessels traversing a busy body of water filled with critical submarine cables.

And we’re not out of the woods yet. Merchant ships in the Red Sea are still being targeted, and it is not out of the question that we could have another vessel, struck by a missile, inadvertently cut another submarine cable. The loss of another major submarine cable connecting Europe to Asia would be devastating — there are only a few of them in total.

Lastly, spare a thought for the crews of the cable ships sailing into these dangerous waters to make the repairs necessary to keep international communications flowing. The Houthi Yemen Minister of Telecommunication recently released a statement emphasizing the requirement that cable ships obtain a permit in order to carry out repairs in the Yemeni territorial waters where his government continues targeting ships with missiles and armed drones.

The permits, he adds, are “out of concern for (the ships’) safety.”